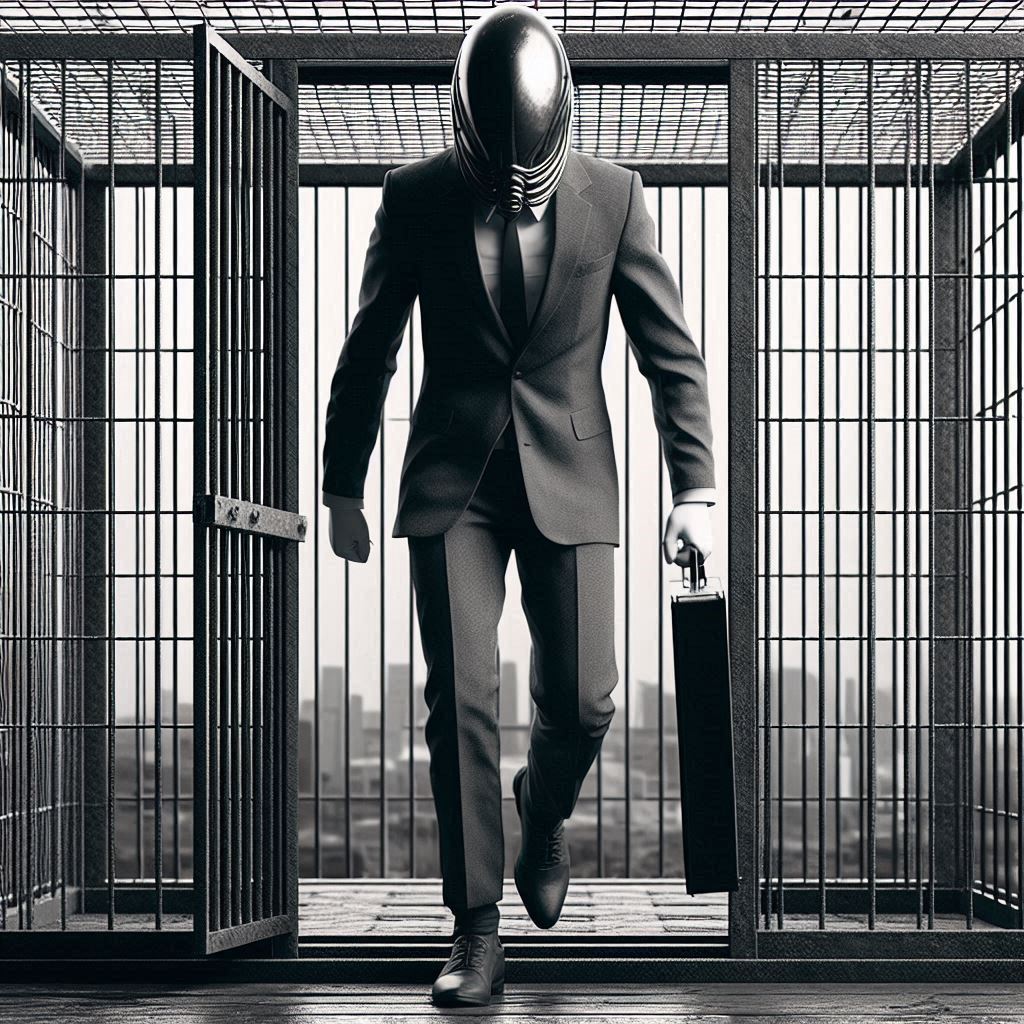

In our day-to-day searching for solutions to optimize operations, improve efficiency, reduce costs, and keep our customers happy, we find ourselves having to choose between different options. One of the concepts that is often used to make this selection of solutions is “lock-in”. The term lock-in refers to a company’s dependence on a specific vendor, technology or platform, so that when we go to switch to another option, we encounter barriers that may be of an economic, technical or other nature.

The truth is that in most discussions where lock-in comes up, the first thing that is said is “lock-in must be avoided at all costs”. The fact is that, like cholesterol, there is “good” lock-in and “bad” lock-in. This sometimes unavoidable phenomenon can have both advantages and disadvantages.

The best thing to do is to make a more detailed analysis before saying yes or no to any type of lock-in, and to be clear that it can be a yes. In fact, we live daily with this phenomenon. When we buy a house, apart from having to pay certain fees and taxes, it has other implications. It is good to have the security of a home of our own, but if we suddenly have problems with the neighbor, if the neighborhood becomes dangerous, if the house is a ruin… we have a lock-in, since we cannot move quickly to another house. Another everyday example is marriage. You have certain barriers that prevent you from quickly going to another one. But marriage has good things (yes, for real) and bad things. If people are married, it means they saw more benefits than risks. And that doesn’t mean that there are no divorces, but when you get married, you have to take into account that divorce is then possible.

Within the company it’s the same thing. We have multiple areas where a lock-in can occur. Some of these areas could be:

- Software: For example, a company decides to implement a CRM, where it will keep all its customer information and integrate it with its sales and marketing processes. If the CRM provider raises the price of licenses exorbitantly, considering switching to another CRM would mean retraining staff, moving data from one CRM to another and buying new licenses among other tasks. We will think long and hard before migrating, resulting in a significant lock-in.

- Material or people suppliers: If our company is in production, we can purchase all our components from a single supplier, thus optimizing the supply chain and obtaining volume discounts. If the supplier now starts to become less reliable in deliveries, changing supplier will mean a complete overhaul of the supply chain, which is not easy and also very costly, resulting in a lock-in with that supplier.

- Cloud Providers: If we decide to go with the services of a certain cloud provider, switching to another provider could mean having to rewrite applications, train personnel and migrate data and connections, which is a costly and complex process.

- Internal staff: We can find people who have accumulated a lot of unwritten knowledge about an area of the company and who are indispensable to perform a certain process, or to manage a software. The company depends on this person who is not so easy to replace, having lock-in with that worker.

Surely some cases have already come to the reader’s mind from their daily experience, but if not, let’s think about these two clear examples. When investing in an iOS mobile device, its App Store apps, and services such as iCloud, switching to Android will be costly and complicated. Users not only have to buy new devices, but also migrate data, learn the new system, and possibly lose access to purchased apps and content. But while remaining in the Apple ecosystem, integration and use of services is seamless. Another clear example is Microsoft, which for years dominated the office software market with its Office suite. The .doc, .xls and .ppt files became de facto standards, creating a significant lock-in for all companies that depended on these formats for their documents. But it was and still is accepted for the benefit of using this suite.

Is lock-in really that bad?

Admittedly, it usually has its downside. Thinking about the examples above and many others that may come to mind, we will find negative patterns that repeat themselves in them:

- Limitations to innovation and customization: Lock-in can restrict a company’s ability to adopt new emerging technologies or innovations from other suppliers that could offer competitive advantages.

- Risk of obsolescence: Linked to the previous point, if the supplier fails, is acquired or simply stops innovating, the company may be left with obsolete technology that is difficult to replace.

- Long-term high costs: If a supplier knows that its customers are locked in, it could raise prices or reduce the quality of service, knowing that the company has few viable alternatives.

- High exit costs: When a company decides to migrate away from a lock-in provider, it often faces significant costs associated with the transition. This includes direct costs, such as purchasing new licenses or hiring migration services, and indirect costs, such as staff training and adapting to new systems.

Is it all bad?

No, it’s not all bad. Sometimes it is good to accept a lock-in if the advantages it offers outweigh the disadvantages it brings. As well as the disadvantages, the advantages can be very varied, for example:

- Stability and predictability: Lock-in can provide a stable and predictable technology environment, allowing companies to plan for the long term with greater confidence.

- Strategic supplier relationships: Companies can develop deeper relationships with their suppliers, which can lead to better support, early access to new features and possible discounts.

- Operational efficiency: By standardizing on a specific platform or technology, companies can streamline their processes and increase operational efficiency such as offering more specialized technical support and regular updates, ensuring that the system remains secure and up-to-date.

- Deep integration: Lock-in often results from deep integration between systems, which can provide advanced functionality and a smoother workflow.

- Economies of Scale and Discounts: Engaging with one vendor over the long term can result in significant discounts and economies of scale, reducing overall IT costs.

So how do we deal with lock-in?

Above all, by analyzing and making informed decisions. When making a decision that could lead to a possible lock-in, it is important to analyze the pros and cons of that decision. If we see that the benefits of that decision outweigh the disadvantages detected, it is a possible solution to take.

One of the key points of this analysis should be whether or not there is really an exit from this lock-in and what would be the cost (material, personal, temporary, etc…) of the exit. Usually, these possible exits appear during the analysis as mitigations to the most important risks. Another important section is to establish the moment at which the exit should be activated. Let’s take a simple example:

We have two technologies that help us reduce operating costs and we have to analyze them:

Technology A: Annual cost 100. Operational savings 200.

Technology B: Annual cost 50. Operational savings 100.

Total cost of migration from A to B 100 (technical cost, personnel cost, possible shutdowns, training, etc…).

On an economic level, technology A is better, since I have a profit of 100 (200-100, compared to 100-50 for technology B) in my account compared to the 50 that I would have with technology B. Although it is more expensive and has lock-in, it gives me more savings in my operations, specifically 50 more savings per year. If I believe that I will keep technology A for at least 2 years, I will have saved 100 more compared to B, which will cover the cost of migration. In other words, after the third year, even if I have to leave that lock-in, I will have benefited from it. If technology B releases a new version that gives me savings of 200 and the costs are raised to 75, this would give me annual savings of 125. Knowing that technology A generates savings of 100 per year and now technology B generates 125 and the migration cost is 100, it would imply that in 4 years I would have covered the investment of migrating from A to B.

We can see that there is an exit from the lock-in of technology A, and it remains to specify when to activate this exit. We can think of something like when the return on investment of moving from technology A to technology B (or whatever), is less than 3 years, it would be time to activate the exit.

If this were the case, in the example above the exit strategy would not yet have been activated, but if they kept the annual cost at 50 in technology B, the annual savings would be 75 over technology A, so the ROI would be in less than two years. Time to start preparing the migration project.

Of course, money is not worth the same in year 1 as in year 5, technology A may change and provide more savings, and there are many other variables that affect this case, but to simplify the example we have not taken them into account.

As aspects to take into account to fall as little as possible in the lock-in, we have:

- Adoption of Open Standards: Using technologies and platforms that adhere to open standards can facilitate interoperability and migration between different systems. This will facilitate future actions.

- Vendor and Technology Diversification: Whenever possible, work with multiple vendors to reduce dependency on a single vendor and increase flexibility.

- Migration Planning: From the outset, companies should plan for possible migrations (look for the exit), including detailed documentation of systems and processes. This can reduce costs and complexity in the event of a future transition.

- Contract negotiation: When entering into agreements with suppliers, negotiate clauses that facilitate migration or access to their data in standard formats.

- Investment in training and documentation: Maintain a solid, up-to-date, written internal knowledge of systems and processes to reduce reliance on specialized external support or specific internal individuals.

- Long-term planning and regular evaluation: Before adopting a new technology, carefully evaluate the long-term implications and possible exit scenarios. Conduct regular assessments to identify lock-in areas and plan mitigation strategies.

Lock-in is a reality of our daily lives, both in the professional and personal environment (remember marriage or the purchase of a house). It is important to analyze well the advantages it can bring and check that they really outweigh the inherent risks.

It is important to be aware of these risks, and consider strategies to mitigate them. In the end, the key is to find a balance that maximizes the benefits while minimizing the disadvantages.

Ultimately, technology lock-in is neither inherently good nor bad; it is a reality that must be managed. Companies that understand its implications and plan when and how to exit lock-in will be better positioned to take advantage of its benefits while mitigating its risks, thus ensuring their ability to innovate and adapt to constant change.

I never thought of marriage as a lock in…. but it is 😀