We are all aware of the uncertainty in which we constantly live. The famous VUCA environments (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity). With the advent of Generative AI, new ways of performing tasks and business models (which we will discuss another day) appear every week.

Under these conditions, it is impossible to predict the future, but we can always prepare for multiple versions of it. Scenario planning can help us do this.

In his book The Art of the Long View, Peter Schwartz explores how scenario planning can transform the strategy of any company (and person), explaining the benefits of this tool for dealing with complexity, mitigating risks, and discovering opportunities.

What is scenario planning and why is it useful for businesses and individuals?

Scenario planning began during World War II as a method of military planning. It basically involves creating coherent narratives about plausible futures based on factors such as political, economic, technological, social, and regulatory trends (a PESTEL analysis could be used as a complementary tool). The aim is not to predict the exact future, which is impossible, but to imagine different contexts in which we may find ourselves in the future, so that we can make informed decisions as we approach any of these scenarios. According to Schwartz, scenarios help companies to:

- Broaden strategic perspective: By exploring multiple futures, companies avoid the bias of thinking linearly or assuming that the present will continue unchanged.

- Identify risks and opportunities: Scenarios reveal vulnerabilities and areas of growth that might otherwise go unnoticed. They uncover opportunities for innovation.

- Foster adaptability: By preparing for different contexts, companies develop flexibility to respond to unexpected changes.

- Improve decision-making: Scenarios provide a framework for evaluating strategies and decisions under different conditions.

- Technological resilience: Through scenarios and business architecture, we can break down the company into functional blocks and support them with modular technological architectures that can be adapted to each scenario.

According to Schwartz himself,

“this gives us the ability to act with a well-informed sense of risk and reward, which separates both the business executive and the wise individual from a bureaucrat or a gambler.”

A classic example, which is also mentioned several times in the book, is the case of Royal Dutch Shell. In the 1970s, Shell used scenarios to anticipate the oil crisis. While its competitors assumed stability, Shell imagined a drastic price increase, which allowed it to diversify and strengthen itself, becoming one of the most important companies in the sector. Companies can apply the same approach that Royal Dutch Shell applied in the past. In order to understand how scenarios work, let’s imagine that we are an insurance company that wants to know how to face challenges such as digitization or the evolution of cyber risks.

The scenario creation process for an insurance company

Based on Schwartz’s principles, the main steps to follow for scenario planning would be:

- Define the focus, the strategic question, and the time horizon

Identify the key technological challenge. For example: “How will AI and cybersecurity impact our architecture in 2035?” The time horizon should be far enough in the future to capture significant changes, but realistic for planning purposes. A horizon of about 7-10 years allows us to capture significant trends without falling into speculation.

When defining scenarios, it is always a good idea to start from the inside out rather than from the outside in. That is, start with a decision or issue to analyze, and build the scenario around it. What are the issues we need to decide will have an impact in the future? Then see how other factors impact these issues.

Another example of a key strategic question could be: “With the technological changes that are taking place, should we change the insurance portfolio we offer?” We can also define the scope at the level of areas of the company, for example, focusing on health or property insurance.

- Identify driving forces

Driving forces are external factors that will influence the sector. These will vary depending on the sector. We can base our analysis on Porter’s forces, PESTEL analysis, etc. This list is usually drawn up in heterogeneous groups in order to capture as many ideas as possible. Later, with smaller groups, the driving forces with the greatest impact and importance for each case are selected and reduced to a list of around 10. In the insurance sector, these could include:

- Technological: Adoption of artificial intelligence to assess risks or blockchain for contracts.

- Economic: Economic growth or recession affecting demand for policies.

- Social: Demographic changes, such as an aging population demanding more health insurance.

- Regulatory: New data privacy laws, capital or technology requirements.

- Cyber: Increase in ransomware attacks or data breaches.

Schwartz distinguishes between inevitable trends (such as population aging or technological advances) and critical uncertainties (such as AI regulation).

- Select critical uncertainties

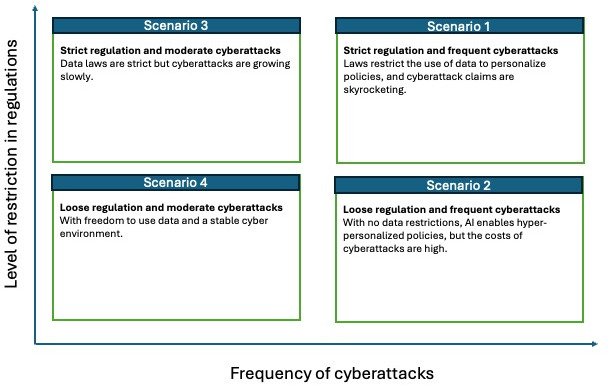

From the driving forces, the two most uncertain and highest-impact variables are chosen. This is sometimes difficult to do, as they are uncertainties. Working with small, diverse groups of people from different areas of the company yields better results. For an insurance company, these could be:

- Uncertainty 1: Will there be strict regulations on the use of data to personalize policies?

- Uncertainty 2: Will the frequency of cyberattacks increase exponentially?

These variables create a 2×2 matrix with four possible scenarios.

- Build coherent narratives

Each scenario should be a detailed and plausible story, taking into account the quadrant of the matrix we are in. Some summarized examples for the scenarios would be (in a real case, a more detailed history must be carried out so that the weak signals we will see later can be better identified and linked):

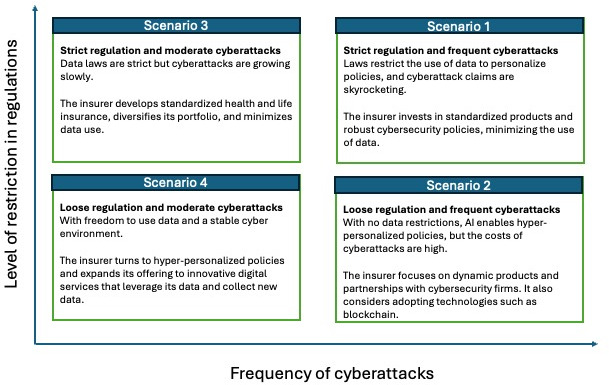

- Scenario 1: Strict regulation and frequent cyberattacks: Laws limit the use of data to personalize policies, and claims from cyberattacks skyrocket. The insurer invests in standardized products and robust cybersecurity policies, minimizing the use of data.

- Scenario 2: Loose regulation and frequent cyberattacks: With no data restrictions, AI enables hyper-personalized policies, but the costs of cyberattacks are high. The insurer focuses on dynamic products and partnerships with cybersecurity firms. It also considers adopting technologies such as blockchain.

- Scenario 3: Strict regulation and moderate cyberattacks: Data laws are strict, but cyberattacks are growing slowly. The insurer develops standardized health and life insurance, diversifies its portfolio, and minimizes data use.

- Scenario 4: Loose regulation and moderate cyberattacks: With freedom to use data and a stable cyber environment. The insurer turns to hyper-personalized policies and expands its offering to innovative digital services that leverage its data and collect new data.

Each narrative should detail the context (economic, social, technological) and the implications for the company.

- Analyze implications and design strategies

Assess how each scenario affects the company, for better or for worse. What strategies work in all cases? For example, investing in cyber risk analysis technologies would be a robust strategy, as it will be useful in all scenarios. Others, such as developing AI-based policies, could be prioritized in scenarios with lax regulation.

- Monitor weak signals

Schwartz highlights “weak signals,” early indicators of change. For example, an increase in local data privacy laws could point to the “strict regulation” scenario. Companies should track these signals (news, regulations, cybersecurity reports) to adjust their strategy.

These scenarios should be revisited regularly, taking into account the signals that the environment is sending us, and adapted according to the context and the company’s actions as they develop.

Practical examples

We have seen an example of a scenario within the insurance sector, but there are countless others:

- Property insurance: An insurer could create scenarios based on the adoption of IoT technologies and the evolution of urban risks. In a “dominant technology” scenario, it would use sensors to adjust premiums in real time. In a “growing risks” scenario, it would prioritize policies with broad coverage.

- Health insurance: Scenarios could explore the impact of telemedicine and public health policies. In a “digital health” future, the insurer would offer policies integrated with wearables. In a “traditional care” scenario, it would focus on plans for aging populations.

- Cyber insurance: An insurer could anticipate cybersecurity regulation and an increase in attacks. In a “strict regulation” scenario, it would develop products to comply with new standards. In a “massive cyberattacks” scenario, it would prioritize policies for technology companies and small companies.

Similarly, we can think of scenarios in many other sectors, for example:

- Energy sector: A renewable energy company could create scenarios based on the adoption of climate policies and advances in energy storage. One scenario could imagine a future where subsidies for renewables disappear, forcing the company to innovate in terms of costs. Another could foresee a massive adoption of advanced batteries, driving demand for solar solutions.

- Retail and e-commerce: A supermarket chain could explore scenarios based on the growth of online shopping and consumer habits. A “digital dominance” scenario could lead them to invest in automated logistics and e-commerce portals, while a “return to local” scenario could prioritize physical stores with unique experiences.

- Technology sector: A software company could use scenarios to anticipate the impact of data regulation. In a “strict privacy” scenario, the company could develop solutions that prioritize data security. In an “unrestricted innovation” scenario, it could focus on AI-driven products without worrying about legal constraints.

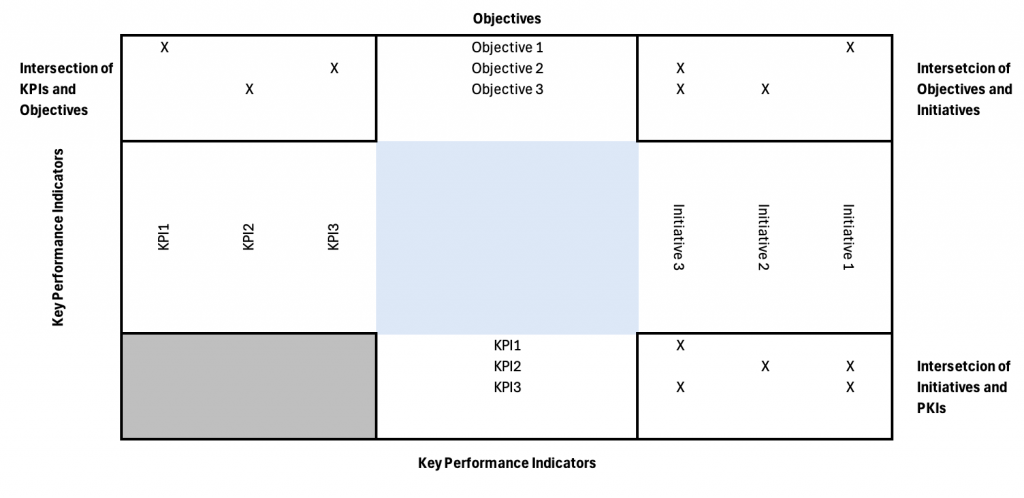

How scenarios enhance strategic execution through business architecture

We have seen how scenario planning allows companies to imagine plausible futures and make strategic decisions in the face of uncertainty (such as data regulations or cyberattacks). However, transforming these visions into concrete results requires effective execution at scale, a challenge addressed in The Execution Challenge: Delivering Great Strategy at Scale by Peter Leinwand and Cesare Mainardi. This book emphasizes that a successful strategy depends on aligning capabilities (key competencies of the company), value streams (processes that deliver value to the customer), and initiatives and their projects through a coherent business architecture. This integration ensures that technology decisions are implemented with a clear objective and measurable impact.

Business architecture acts as a framework that connects strategy with execution, mapping capabilities and value streams. Scenarios enrich this framework by identifying which capabilities are critical in different futures. For example, in a scenario of “strict regulation and frequent cyberattacks,” an insurance company would prioritize capabilities such as data governance and real-time threat detection, while in a scenario of “lax regulation and moderate cyberattacks,” it could focus on capabilities for policy customization using AI. The Execution Challenge emphasizes that success lies in concentrating resources on a small set of differentiating capabilities, avoiding dispersion across unaligned initiatives.

Value streams benefit directly from the scenarios, as they help redesign processes to adapt to uncertain futures. For example, the “policy underwriting” value stream could be optimized with AI to automate risk assessments in a flexible regulatory scenario, but would require robust manual processes in a strict regulatory scenario. According to The Execution Challenge, value streams must be agile and supported by technological capabilities, and must be able to adapt to different scenarios. Scenarios guide the selection of initiatives and projects, ensuring that they are relevant in multiple futures.

Initiatives and projects must be rigorously prioritized to maximize strategic impact, as proposed by Leinwand and Mainardi. Scenarios facilitate this prioritization by simulating the performance of each initiative in different contexts. For example, a project to implement DevSecOps could be critical in a “frequent cyberattacks” scenario, reducing the cost of data breaches (as in the insurance example, it is worth noting that, according to IBM 2024, the average cost per data breach is $5.9 million). In a “moderate cyberattacks” scenario, the insurer could redirect resources to AI initiatives for personalization. This approach aligns with the principle of “doing less, but better,” ensuring that projects reinforce essential capabilities.

Scenarios and business architecture are also complemented by continuous monitoring. By using clear and measurable objectives, we will have KPIs available that will help detect the weak signals that Schwartz highlights to determine changes in context, allowing for agile adjustments. For example, a signal of stricter data regulations could lead to reconfiguring the underwriting value stream to prioritize compliance, relying on data governance capabilities.

Benefits and challenges of scenarios

Scenario planning offers clear advantages: it improves preparedness for emerging risks, encourages product innovation, and strengthens resilience. However, it requires time, resources, and overcoming the bias toward favoring the most likely scenario. Schwartz emphasizes that all scenarios must be explored with equal rigor.

The biggest benefit is cultural: scenarios promote creative and proactive thinking, which is essential in any industry where risks and opportunities evolve rapidly (sometimes I wonder if there is any industry where this is not the case). As Schwartz said,

“The future is not predicted, it is invented”